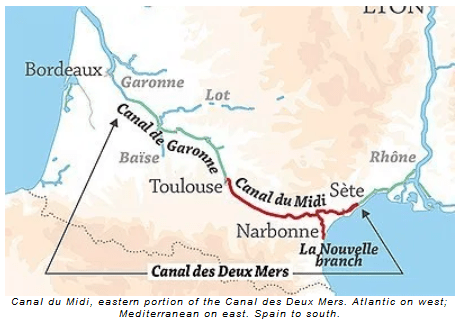

From the enormous port de l’Embouchure (mouth of the port) in Toulouse, you cycle under the bridge and out on to the Canal du Midi’s towpath. From here, you pass the urbanisation of Toulouse and the rail station, Gare Matabiau, a statue of Riquet farewelling you as you leave.

The canal weaves through the city suburbs and out into the fertile countryside until it reaches Escalqueuns. Following is Ayguevives Lock with its mill dating from 1831, then on through Sanglier Lock to Negra Lock. This was a ‘dinee’, a lunch stop, for passengers on the canal. A small village was built here to cater for those travellers; hotels, restaurants and stables, even a church, which has been well preserved.

There are three villages along this stretch, two beautiful and one eccentric. They are Montesquieu-Lauragais, with its two castles, and Villenouvelle and its superb bell-tower. On the other bank, Saint Rome is where an eccentric architect built a village in an assortment of styles: Moorish, Flemish, Neo-Byzantine, and also Baroque and Tudor for good measure.

It’s then back to the canal and normality, crossing the beautiful Lers Aqueduct, designed by Jean-Polycarpe Maguès, who was the engineer responsible for overseeing the construction of the canal itself.

Then it’s on to the ‘summit’, so called because it is the highest part of the canal. The Seuil de Naurouze is where the supply of water to the canal is controlled by a series of sluices. Here is both beauty and history, an Arboretum, a spectacular avenue lined with 62 plane trees leading to a tribute to Paul Riquet, a tall obelisk; the place where a Napoleonic general surrendered to Wellington after the Battle of Toulouse and where an ancient Cathar fortress still stands. It also marks the regional border where the Haute-Garonne department of the Midi-Pyrenees become the Aude department of Languedoc-Roussillon.

After Seuil is Mediterranean Lock; now you stop being an ‘upstreamer’ and become a ‘downstreamer’, the water now running towards the Mediterranean. The hillier terrain is noticeable and the locks more frequent as the canal begins its gentle descent to the Mediterranean.

One of the major ports on the canal is Castelnaudary, a picturesque town and ‘Grand Bassin’, famous for its cassoulet. It’s now a slow meander through this peaceful landscape, pretty villages lazing under a warm sun.

The next stop is the UNESCO-listed fortified city of Carcassonne. This is an ideal base for an overnight stop, as Carcassonne is a must-see, and it’s just a brief detour from the Bastide Saint-Louis, the town through which the canal actually passes.

From here, the canal – itself World Heritage Listed – closely follows the course of the River Aude through the gentle, hilly landscape of the Aude valley. This part of the canal is lined with ancient villages, their gothic and medieval churches, castles and ramparts all of interest.

There are some attractive locks, too, well tended by the ‘eclusier’, the lockkeeper; some, like Puicheric and Jouarres, provide cafes and ‘produits terroir’ (local produce) for sale. There is also Ecluse Aguille, where the lockkeeper has turned his lock into a fascinating gallery of sculptures in metal and wood, also carving figures and faces in surrounding trees.

The small port of La Redorte was a ‘dinee’ for early travellers, and the tradition continues today with a quayside restaurant. From here it’s on to the once major port of Homps, now a large centre for pleasure boats, with plenty of accommodation and restaurants, and lots of bustle in the port itself.

Farther down is the first canal bridge to be built in Europe, the Répudre Aqueduct, which crosses the river Répudre. A few kilometres on is the delightful port of La Somail, which seems to look very much like it would have 300 years ago when it was an overnight stop.

As you near Béziers, the canal weaves its way somewhat erratically through what was difficult countryside to cut a canal; the number of curves increases, sharp bends wend their way, and aqueducts abound – seven in total between Argeliers and Capestang. Other great feats of engineering are here, too: the first canal tunnel at Malpas and the Fonsérannes ladder, a succession of 8 locks for boats to negotiate, rising over 21 metres in the space of 300 metres.

Béziers signals the last leg of the journey. Between here and the Mediterranean are the towns of Villeneuve-Lès-Béziers, and the picturesque Agde, founded 2500 years ago by the Phoenicians and today an architectural treasure trove. It is after Agde that you can smell the sea, the last 12 kilometres a cycle lane between the Bassin de Thau – a large saltwater lake – and the Mediterranean that leads you into the port of Sète and the end of your adventure.

Iain Griffiths is the author of A Cycling Guide to the Canal de Garonne and the Canal du Midi, available for Kindle. Iain worked as a freelance cameraman filming new stories, and natural history and travel documentaries worldwide before retiring to France. His passions include cycling, photography, watercolour, and mountain walking.

Guide can be purchased from Amazon Books — CLICK HERE